What makes an ICM image work?

I’ve recently been working on a project where I experimented with intentional camera movement (ICM). ICM uses controlled (‘intentional’) camera movements during exposure to create shape, rhythm, and atmosphere through blur.

I’ve tried ICM in the past, but I didn’t pursue it because it felt like composition roulette. Perhaps 1 in 50 of my images looked interesting and painterly — but that one wasn’t interesting or painterly enough to motivate me to continue.

More recently, I joined a critique circle where members take an ICM image and share it with the group for appraisal. This meant it was time to return to the technique.

Before I describe what I learned in this project, I’ll be sharing 10 images. I created half of them using ICM and the rest by simulating ICM in Photoshop. Then I’ll share what I think makes a good ICM image.

Woodland

This is an ICM image made in camera (using my phone). I found that vertical movements emphasised the shape of the tree trunks.

Perth skyline

This is an ICM simulation I created in Photoshop. I made the original image a few years ago during a trip to Australia. There was gorgeous evening light on the buildings.

Minster Pool

This is an in-camera ICM image that I made in Lichfield. I used the Slow Shutter app on my phone. I find I get a better hit rate with this app compared to using my camera. I think this is partly because I see the image build up in real time, partly because the screen is larger than the one on my camera and partly because it's easy to delete the image and try again.

The Shard

This image was created in Photoshop. I can’t say there’s a fixed way I do it: it’s very much image dependent. But essentially, I turn the image into a smart object and add some motion blur at 90-degrees. I then duplicate the smart object and change the extent of the motion blur to something longer or shorter. I then change the blend mode to something that looks right. Sometimes a couple of blend modes work well, so I’ll do a stamp visible layer for each of those and mask in the parts I like. I’ll then add some textures and maybe a LUT. I might take it into a plug-in like Nik Color Efex and see if that creates an interesting effect.

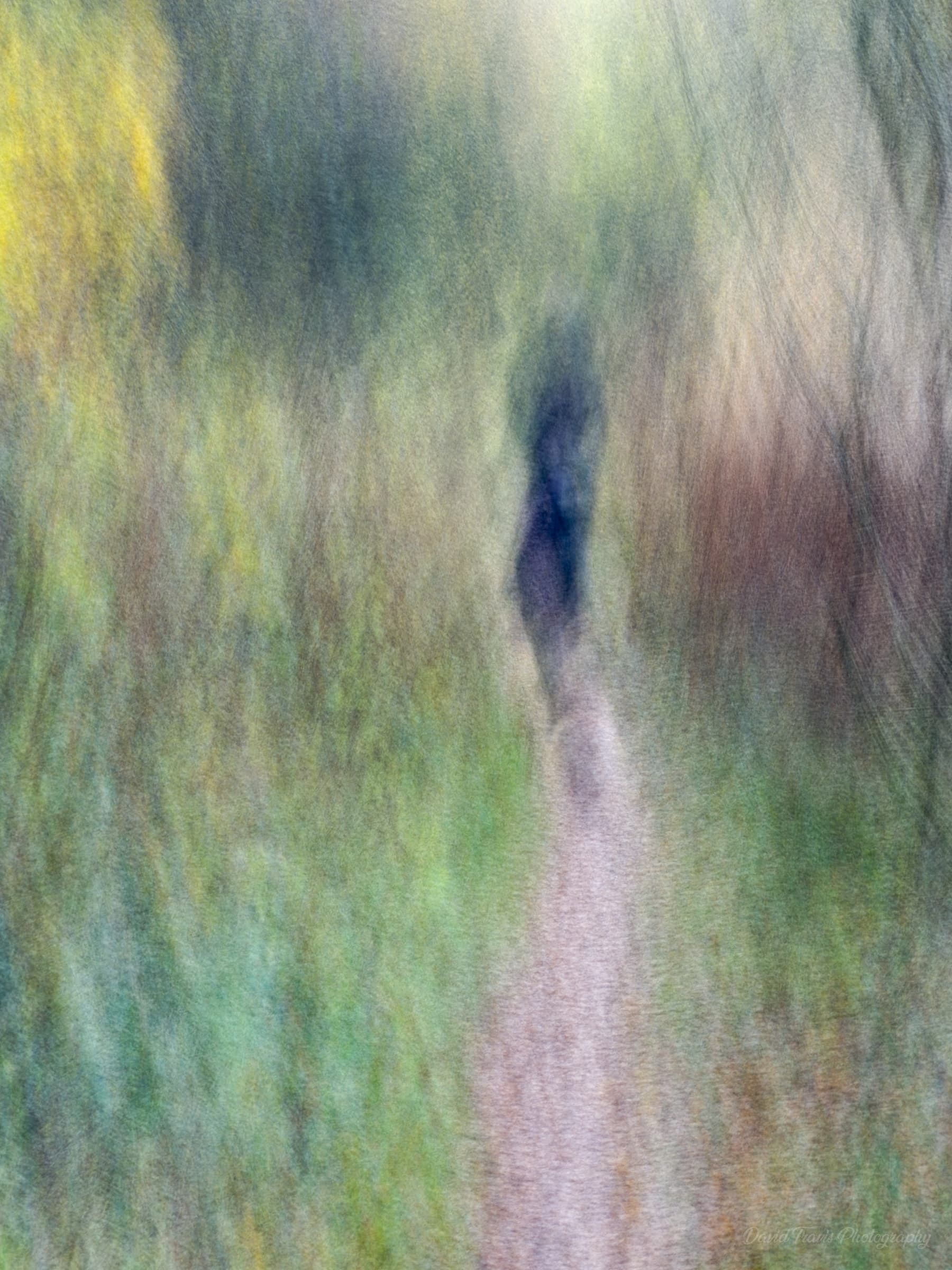

Phantom

This was created in camera. This person was walking in front of me while I was out on a dog walk.

Gladstone Pottery Museum

This was created in Photoshop. I end up with several layers and I deliberately flatten the image so I can’t reuse what I’ve done as a formula. I want to make sure that I always do it by feel. I find that it only works on certain mages — there are some that I think should have promise but I can’t get the effect to work.

Vortex

I made this in camera on a walk near Hathersage. I noticed the light on the stream reflected from a beech tree. It was a bright, sunny day, so the trunk was in full sun but the stream was mostly in open shade. I changed my position to make the reflection fall where the water was cascading over the stepping stones. I took a number of ‘straight’ images with my mirrorless camera at various shutter speeds but I also liked this ICM version I took with the Slow Shutter app on my phone. I kept the movements subtle as I didn’t want to obliterate the cascade.

Looking out, looking in

A Photoshop simulation of the ICM effect applied to the London Eye.

Canal path

I created this in camera. I was aiming for a painterly, Turner-esque feel to the image. There's enough motion to remove the sharp edges but I think there's still enough detail for you to work out what's pictured.

Light and memory

This final image was created in Photoshop. It shows the Thames Barrier taken from Millwall.

In this project, I think there are a few answers to the question ‘What makes a good ICM image?’ The first are around technique, and the second are around artistry.

Technique: “Follow the energy”

One thing I discovered is that the word ‘intentional’ in intentional camera movement is doing a lot of heavy lifting. It’s obviously there to distinguish it from unintentional camera movement: that is, movement due to poor camera technique. This happens when you hand hold a camera, intending to get a sharp image, but the exposure time is so long that the image ends up unintentionally blurred.

But I also think the word is there to encourage ICM photographers to respond to the scene in front of them. As a simple example, my woodland ICM images seem to work best with vertical movements of the camera, elongating the trunks. Moving the camera horizontally just creates a kind of mush. So I think it’s about identifying the energy in the scene, or the energy you want to imbue in the scene, and trying to replicate that with your camera motion.

Artistry: Create a curiosity gap

Moving beyond technique, I think the reason why the best ICM images work is because they create a ‘curiosity gap’: they leave something unsaid in a photograph and make the viewer do some work to complete it.

For the ‘curiosity gap’ to work, images can’t be totally abstract. They need a semi-identifiable object, or at least a pattern that looks like an object so that the viewer can ‘complete’ the work. Successful images also need to obey the basics of composition, like balance, rhythm and flow.

One thing I learnt on this project is that the advantage to creating ICM-style images from ‘straight’ images in Photoshop is that you know you have nailed the composition. And when you start manipulating the image, you can see how far to push things before the image becomes too abstract.

In contrast, it’s tricky to get the composition right when you are moving the camera around: it’s easy to overdo the motion and end up with something unintelligible. Which is why it might take those 50 tries to get one usable picture.

In camera or in software?

All things being equal, I would prefer to create these images in camera rather than in Photoshop. That’s because each person has their own individual way of shaking, rotating or moving the camera. This means each resulting image is unique to the photographer: it’s like a signature. When I do it in Photoshop I’m following a series of steps that anyone could recreate.

But all that really matters is the final image, not how you create it. I enjoy the freedom of exploring a scene with my camera and seeing what emerges — but I’ve found I also enjoy the controlled artistry Photoshop affords.